In terms of size, location, and natural resources Xinjiang has strategic importance to China. In terms of history, people, and culture, Xinjiang is different from many parts of China. This article describes some of the opportunities and challenges facing China with respect to Xinjiang based on observations from a recent two-week visit to Xinjiang. We flew to Urumqi (烏魯木齊), the capital of Xinjiang, located north and east of the central part of Xinjiang. From there except for the last leg, we (group of 14) traveled via our tour group bus. We covered the middle part and the southwestern part of Xinjiang. For the last leg, we flew from Kashgar (喀什), located in the southwestern part of Xinjiang, back to Urumqi.

Our observations are discussed in terms of geography, political history, religion, culture, livelihood, and government structure.

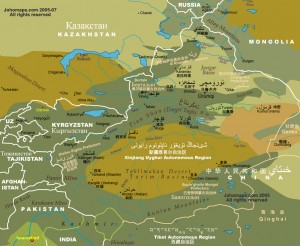

Geography: Xinjiang is an autonomous province in China, officially known as Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Uyghur (維吾爾) is often also spelled as Uygur or Uighur, and is pronounced as wee-gher. It is one of China’s 56 ethnic groups and the largest ethnic group in Xinjiang (more on this later). It is the largest province in China, occupying about 1/6 the area of China (or three times the size of France). However, it has only 22 million people. Compared with the rest of China, it is sparsely populated, since its population density is only about 10% of the average population density in China. Below is a map of Xinjiang, including showing its border countries north and west of Xinjiang.

On its north and west, Xinjiang borders eight countries: Russia, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India. This means that traditionally this area has always had a lot of cross border interactions and therefore it has strategic political importance. Xinjiang is consisted of two basins surrounded by mountains. The Tian Shan Mountains (Heavenly Mountains) run through the middle of Xinjiang, and separate the Jungar (also spelled as Jungariah) Basin in the north and the Tarim Basin in the south. To the north of the Jungar Basin lie the Altay (also spelled as Altai) Mountains. To the south and west of the Tarim Basin lie the Kunlun Mountains, Pamir Mountains, and the Karakoram Mountains. The world’s second largest desert, the Taklamakan (also spelled Taklimakan) Desert and the world’s longest desert highway (340 miles) lie to the south of the Tian Shan Mountains in the central part of southern Xinjiang.

Xinjiang is one of the hottest provinces in China, and the Flaming Mountain (famous from the classic Chinese novel “Journey to the West” or “Monkey King”) near Turpan (吐魯番) is the hottest place in China, with air temperature often reaching above 120 degrees, and the mountain surface temperature reaching over 160 degrees. Xinjiang is also very windy, making it ideal for windmill farms, and has the world’s second biggest windmill electricity generating industry (second only to Holland).

Xinjiang is also rich in natural resources. For example, it has approximately 30% of China’s oil reserves, and it has the largest gas reserves in China. Because of its large size and small population, the Lop Nur site in Xinjiang was chosen to be the site of the first China nuclear bomb test in 1964.

Political History: Xinjiang has a complex political history. Approximately as early as 2,500 years ago, nomadic tribes of various origins and cultures migrated to various parts of current Xinjiang. For example, nomadic tribes of Indo-European origin migrated to especially western part, and nomadic tribes of Mongolian origin migrated to especially northern part.

There were many military struggles between various tribes and also between these tribes and China and other countries, e.g.,

- Around the first century B.C., Han Dynasty controlled Xinjiang on and off for about 200 years

- Around the seventh century A.D., Tang Dynasty controlled Xinjiang for about 100 years

- Xinjiang was also under the control of Tibet (e.g., during the eighth century A.D.) and under the control of Mongolia (e.g., under Genghis Khan and the Yuan Dynasty starting around the 13th century A.D.)

- Qing Dynasty controlled Xinjiang around the 18th century A.D.

- From 1871-1881, parts of Xinjiang was under the control of Russia

Many of the wars associated with these military struggles were extremely cruel and deadly to the defeated parties.

Around 1882-1884, Qing Dynasty established Xinjiang as a province and dropped the name Huijiang or Muslimland. In 1912, the Republic of China “controlled” Xinjiang, but a short-lived East Turkistan Republic existed in 1933-34, and a Second East Turkistan Republic with Soviet Union support existed in 1944-49. In 1949, the People’s Republic of China took control of Xinjiang, and in 1955 established the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.

Thus we see that Xinjiang has a long history of conflicts and allegiance to various countries. Coupling that with differences in culture, religion, and language between the Uyghur minority ethnic group and the Han majority ethnic group could lead to potential political unrest. We will come back to this issue later.

Religion: Buddhism was first introduced to China via Xinjiang from Kashmir around the first century B.C. Shortly after, partially because local rulers promoted it, Buddhism became the main religion in Xinjiang. Then in the late ninth century A.D., Islam spread from central Asia to southwest Xinjiang. Again, because local rulers promoted it, Islam spread in Xinjiang.

In the 10th century A.D., after a major religious war between an Islam local kingdom and a Buddhism local kingdom that was won by the former, Islam gradually replaced Buddhism. From around the 13th century A.D., Islam became the dominant religion in Xinjiang, although other religions also existed and still exist, e.g., Buddhism, Taoism, Protestantism, Catholicism, as well as early native primitive religions.

Before Islam became the predominant religion in Xinjiang, Buddhism had a strong foothold and a widespread following in Xinjiang. A major historical relic of the importance and dominance of Buddhism for about a 1,000 years in Xinjiang is the Kizil Thousand Buddha Grottoes found northwest of the city of Kuqa (庫車) near the middle and western part of Xinjiang. There were 339 caves with many Buddhism murals around the walls of the caves, and 236 of these caves still remain today. The murals in the Kizil Thousand Buddha Grottoes date back to the first century B.C., and surpass other Buddhist murals found in other caves in China in its abundance in content, quantity and duration. The fact that the Buddhist grottoes were located here was not by accident, because the Kuqa-Korla (庫爾勒) region (Korla is a city just east of Kuqa) was a communication hub of the ancient Silk Road; this region was the political and economic center of the Xinjiang region as well as the focal point of Central Asian and Indo-European cultures. As a matter of fact, the Iron Gate Pass, which is a strategic check-point on the ancient Silk Road in the middle of Xinjiang connecting west and east, as well as north and south, is near Korla.

Incidentally many of the murals were looted by an enterprising German in the early part of the 20th century, as well as by locals. The murals looted by the German are now displayed in a museum in Europe. As a matter of fact, the Chinese government had to go to this museum and took photographs of those murals, so they can have in China an electronic reproduction of those original murals, although we did not see any of those electronic reproductions.

At the site of the Kizil Thousand Buddha Grottoes is a statue of Kumarajiva, who was a Buddhist scholar (344-413 A.D.) whose father was Indian and whose mother was a Chinese princess from Kuqa. When he was 7 years old, his mother became a Buddhist nun, and he spent the next years following her and studying Buddhist doctrine in Kuqa, Kashmir, and Kashgar. By explaining his deep understanding of many sacred Buddhist texts to a large team of many Chinese Buddhist monks and Chinese translators, he led this team to provide a much better and more detailed translation of many sacred Buddhist texts.

Culture: The Uyghur (維吾爾) language is a Turkish language popular in central Asis, including Xinjiang, Mongolia, Turkey, and several former countries from the breakup of the Soviet Union, such as Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Turkistan, Kazakhtan, Kyrgystan, and Tajikistan. Uyghur and Mandarin are official languages in Xinjiang. The current dominant religion is Islam.

Appearance is middle-eastern and Caucasian, often tall, slender, with facial features that are more European, and hair is often curly and of color tan or with a tint of reddish. Women like scarves, colorful dresses, and high heels. Both men and women like hats. Food, music, and dancing are important. Food is known for lamb kebabs, homemade noodles, baked flat circular bread (known as nang), thin-skinned baoxi, tomatoes, eggplants, grape wine and raisins, Pomegranate juice, and various fruits. People are friendly.

Traditionally they were nomads and merchants (more discussion of their livelihood in the next section).

Today, about 45% of the 22 million population are Uyghur, and about 41% are Han. At the time of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the Uyghur ethnic group was about 90% of the population. Most of the recent people moving into Xinjiang are Hans. As in other provinces and areas in China, the one-child rule is exempt from minority ethnic groups.

Livelihood: The people in Xinjiang were traditionally nomadic people, and many still are involved in agriculture, in farming and animal husbandry. Xinjiang is the largest producer of cotton in China, and has the largest tomato processing and export base, and the largest production base of beet sugar in China.

Because the ancient Silk Road ran through Xinjiang, it also has a lot of merchants producing or dealing in trades of various arts and handicrafts, such as jade jewelry, silk, carpets, scarves, small knives. There is also a big industry of producing wines and raisins.

Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, a great deal of infrastructure has been built all over Xinjiang. These include the previously mentioned windmill farms, many many miles of new highways, roads, and railroads, oil pipelines, schools, hospitals, reservoirs, electric grids, telecommunications (both wireline and especially wireless) and computer networks, airports, new cities or expansion of cities, housing, and other utilities. A lot of people are involved in building the new infrastructure, and many other people are now involved in new industries like oil, gas, windmills, besides the traditional iron and steel, coal, and textile industries.

An example of building the new infrastructure is the building of the world’s longest desert highway, 340 miles long, that goes through the world’s second largest desert, the Taklamakan Desert. This was no easy task, as the sand dunes are often over 100 meters high (and some are over 300 meters high), and the great winds move the sand dunes about 150 meters per year. To build this highway, the highway foundation was dug 10 meters deep. They used specially designed fillings. They planted several rows (three to 10 rows or more) of shrubs and vegetation on either side of the highway covered with mats to keep a lot of the sand from getting close to and accumulating on the highway. They built an irrigation system with deep underground wells to provide water to these shrubs and vegetation. They built 108 small houses, separated by a few miles along the highway, for the lived-in couples who are hired to maintain and keep the irrigation system operating properly. In spite of the enormity of the project, they built the highway in about two and a half years from March 1993 to September 1995.

Building large engineering projects is no stranger to the Xinjiang people. The Karez Irrigation System was constructed over 2,000 years ago near Turpan, and is known as the Underground Great Wall. It is considered to be one of the three major ancient irrigation projects in China, with the other two being the Ling Canal (桂林陵運河) near Guilin in the province of Guangxi and the Dujiangyan Irrigation Project (都江堰) in Chengdu in the province of Szechuan. It is actually many systems, with each system consisting of surface runoff channels, vertical shafts to underground canals about 10 meters below the ground surface, and dams. The 10-meter deep underground canals can keep the water cool and fresh and from evaporating. At its peak, the total length was over 3,000 miles long. Today, there are still over 400 such systems around Turpan.

Another major industry in Xinjiang is tourism. With its mountain beauty, its history associated with the Silk Road, and its ancient Buddhist relics, it is a major attraction for tourists. However, tourism business has declined significantly during the last few years. There are several contributing factors. The 2008 Beijing Olympics attracted a lot of visitors to Beijing, and similarly the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai attracted a lot of visitors to Shanghai. The U.S. economy crashed in late 2008 and 2009, followed by a global economic slow down, and the European economy crashed in 2010. The ethnic riots in Xinjiang in July 2009 resulted in a lot of potential visitors going elsewhere or staying home. Therefore, there has been a lot of layoffs associated with the whole tourism industry.

An example of the beauty of Xinjiang is the Tian Shan Mystic Grand Canyon, north of Kuqa. The many magnificent structures cut into the mountains remind me of the Bryce Canyon National Park and the Zion National Park in Utah in the U.S. Another example is the Heavenly Pond (天山天池), 68 miles east of Urumqi, known for its beauty and tranquility. Many Chinese newlyweds like to go there to take pictures with their wedding outfits. On the southwestern border of Xinjiang with Pakistan is K2, the world’s second highest mountain peak at 28,251 feet. It is also known as the Savage Mountain, and is considered by most people as the most difficult and dangerous mountain to climb in the world. K2 is actually one of five mountain peaks in the Karakorum Mountains, which used to be called K1, K2, K3, K4, and K5. All the other four peaks now have their own names, but K2 kept its name as K2.

Government Structure: Xinjiang has an unusual dual governance structure. There is the usual civilian government structure at the level of region (province), country, city. There is also the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), that has jurisdiction over several medium-sized cities, and many settlements and farms across Xinjiang, providing governmental functions such as healthcare, education, and law and order for areas under its jurisdiction.

In many frontier regions, life was harsh, a good governance structure had not been established, and there was very little needed infrastructure. Often, it was the People’s Liberation Army who went to these regions and established order, stability, and built the necessary infrastructure such as roads, schools, hospitals, housing, and various kinds of utilities. The stated goals of XPCC is to develop frontier regions (then hand over governance to civilian government), promote economic development, and ensure social stability and ethnic harmony, and counter the East Turkestan independence movement. It was established in 1954, abolished in 1975-1981 during the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution, and reestablished in 1981 and continues to today. Eventually it should be phased out, but the end is not imminent.

Similar dual structure had also existed in other places such as Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia, but terminated after meeting its objective.

Summary: Xinjiang is an important and interesting part of China, but very complex. It seems that there are two (at least initially) conflicting forces shaping Xinjiang.

On the one hand, from a national perspective (i.e., the country as a whole), it makes perfect sense to move more people from densely populated parts of China into sparsely populated Xinjiang that has abundant natural resources and with strategic defense importance. Recall that the population density of Xinjiang is only 10% of the average population density of China, and Xinjiang borders eight countries, and is rich in natural resources.

On the other hand, from the Uyghur minority perspective, it is natural to develop some resentment to see so many outsiders (mostly Han people) with different language, religion, and culture moving into their region, and often dominating politically and economically.

It is inevitable that the above two forces will lead to conflicts. I think that at least two ingredients must be part of the necessary conditions in solving this dilemma:

- The livelihood of the Xinjiang people, including the Uyghur and other ethnic groups, must be raised substantially and quickly

- The system must allow the Uyghur and other ethnic minorities to reach the upper decision making positions in industries and government

A third ingredient is to have more interracial marriage between Uyghurs and Hans.

Don

As usual I enjoyed reading your articles. I found the third one of particular interest. One question: What is the status of the relationship between the government and the Muslims in this province?

Thank you

Rich

Don,

I really enjoy reading this article, especially with your detail analysis and observation on overall culture, livelihood, religion, and government. The location of XinJiang with all those hostile neighbor and its resources will present a focus point in the coming years.

Marjorie

Don,

A wonderful introduction, to me at least, to this area and its people. Your descriptions are informative and lively; I’ve learned a lot about a culture I hadn’t known much about.

Thank you!

Linda

Hello Don,

Thank you for sharing your experience with us. I enjoyed it immensely. I’m forwarding your article to my relatives with the hopes that it will inspire a trip to Xianjiang too.

Corinne

Hat’s off! Don. Thanks to Corinne who forwarded your Blog. Together with 24 people from different Continents, we embarked on the same trip as yours in 2005. Since then I met a Uighur student in Melbourne and is pursuing her PhD in Germany; I have befriended Han Chinese who grew up in Xinjiang and are presently working and studying in America. Do you have plans to continue the Silk Road route to Central Asia?? My girlfriend, a Fulbright scholar, fluent in Turkish, whose son-in-law is from Kazakhstan would definitely like to join you!! catherine

Rich,

Thanks again for your comments. I apologized for the delayed response, as I have been away in California until last night.

Regarding your question “what is the status of the relationship between the government and the Muslims in this province?”, the answer is complex as I tried to explain in the article that the political history and government structure in Xinjiang are complex. Since the 13th century A.D., Islam has become the dominant religion in Xinjiang, so most of the Uyghur people in Xinjiang are Muslims, although many other religions also exist in Xinjiang (and Buddhism was the dominant religion in Xinjiang for about 1,000 years starting with the 1st century B.C.).

The government respects the Uyghur people as one of the ethnic groups living in Xinjiang, as well as their religion of Islam. Until recently the Uyghur was the dominant ethnic group in Xinjiang, which has now been surpassed by the Han ethnic group. As in other parts of China, the government provides special considerations to ethnic groups besides the majority Han ethnic group. So in Xinjiang, the Uyghur people also receive special considerations such as exemption from the one child policy, more relaxed standards for college admission, etc. However, since governance in China is dominated by the Communist Party, the Uyghur people and other Muslims in China are not necessarily well represented in the top governance structure of China. That is why I wrote that one of the two ingredients necessary to solve the dilemma of more and more Han people moving into Xinjiang is that the system must allow the Uyghur and other ethnic minorities to reach the upper decision making positions in industries and government (the other necessary condition is that the livelihood of the Xinjiang people, including the Uyghur and other ethnic groups, must be raised substantially and quickly).

Don

Hi Don, After reading your terrific recent post on Hong Kong, I was curious if you’d written anything about Uighurs. A search on “Uighurs” was unsuccessful, and a 2nd search on Uighur brought me here.

Thanks for your analysis here!!! It gave me a much needed new understanding of this part of China. In case it’s useful, here’s a story from today’s news about China’s recent decisions about controlling its Uighur population…

“China footage reveals hundreds of blindfolded and shackled prisoners”

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/23/china-footage-reveals-hundreds-of-blindfolded-and-shackled-prisoners-uighur

Tim,

Thanks for your comments. Sorry for not being able to respond sooner, as I have been extremely busy.

From what we know about the western media’s reporting about the events happening in Hong Kong, I suggest that we have to be extremely careful with such reporting, because the message conveyed is almost always an inaccurate message, in the sense that it is biased, reports only part of what is happening, carefully reports only the part that supports the biased message and frequently creates outright lies, and doesn’t report on the essence of what happened, and why those things are happening.

For many years, the U.S.’s policy toward China has always been one that tries to isolate, surround, and weaken China. The U.S. policy in Hong Kong is just part of that policy, and it has been trying to do that for many years in Hong Kong. Relatively speaking, Hong Kong is much less important than Xinjiang, Tibet, or Taiwan. If the U.S. is working so hard in Hong Kong to destabilize the Hong Kong government and weaken China, how much harder would they be working in Xinjiang, where there are differences in culture and language between the Uighurs and Han Chinese. If I were in charge of the government in Xinjiang, I would also take the necessary measures to keep the domestic and foreign instigators from destabilizing my government. One should pay more attention to whether the livelihoods of the people in Xinjiang has improved significantly during the last 70 years.

By the way, what the U.S. is doing to China is similar with what they have been doing to many other countries around the world in the last half century. Just look at how many countries they have worked to undermine or overthrow the government in power. It is especially important to look at whether the people in those countries have had their lives improved as the result of the U.S. actions.

Don

Don,

Thanks again! I’m especially curious about your comments that:

“We have to be extremely careful with such reporting, because the message conveyed is:

1. almost always an inaccurate message, in the sense that it is biased

2. reports only part of what is happening that supports the biased message

3. frequently creates outright lies

4. doesn’t report on the essence of what happened

5. doesn’t report on why those things are happening.”

I’d love to see more details on each of those five comments.

I’m also curious if you’d apply those comments to Science articles about what’s happening in Xinjiang? For example, do you have an opinion about this validity of the following article?

“Mass detentions in Xinjiang province are unconscionable, regardless of who’s affected. But by targeting academics and intellectuals, authorities are robbing Uyghur—and Chinese—society of an important part of its future, she says. “If you remove from your functioning society all of the future scholars, the current scholars, the scientists,” Robinson says, “You’re losing an entire generation of individuals who could contribute to the production of knowledge.”

See: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2019/10/there-s-no-hope-rest-us-uyghur-scientists-swept-china-s-massive-detentions